Introduction

Oil & Gas in the United Kingdom is considered a mature industry in comparison to Malaysia’s. Although Malaysia has assets from the late 1960’s it is only in the last few years that decommissioning work has begun to be fully considered.

When considering a comparative overview, we need to take into account some other key differences between the areas. In the UK the rights to explore and extract are owned and operated by many individual companies and stakeholders. These are held accountable by many regulatory bodies as well as the legislation in the area. For example, the Health and Safety Executive, The Environment Agency, the UK government and legal systems.

Decommissioning is a cost, there is no real economic advantage people to carry out the works, hence the legislative push from the regulators and other interested parties to get it done.

On the other hand, in Malaysia under Act 144 of the Petroleum Development Act 1974 – PETRONAS have exclusive ownership right to the oil and gas reserves of Malaysia, and it also makes them the main regulatory body for upstream activities. (there are some Product Sharing Contracts but PETRONAS retains ownership). (Law of Malaysia, 1974)

Is there a conflict of interest when the stakeholder is also the regulator?

With the estimated costs being so great, there has been a reluctance to decommission. This delay has been attributed to the recent downturn in Oil prices, but also in an effort to see what other regions develop in terms of processes, technology and cost savings. But at the same time the downturn has expedited the volume of potential decommissioning works, as sites become uneconomical to continue. (Milhench, 2015)

It is fair to point out here that PETRONAS have a stake in other regions like West Africa which are in the process of decommissioning and also the Kinsale Energy assets which are currently at decommissioning project planning and award stage in the Irish sea. Meaning they are being held to UK legislation and regulation, learning how this region plans and operates decommissioning projects.

Malaysia is mainly based on the common law legal system as a direct result of being a British colony in the past, although this does not extend to UK decommissioning legislation.

In Malaysia as in the UK, there was no real consideration for decommissioning in the early development of the industry nor in the Product Sharing Contracts. No legislation directly addressed end of life facilities. With the increasing number of depleted fields in both regions decommissioning has become a key topic for both Government and Operators.

International and Regional Obligations

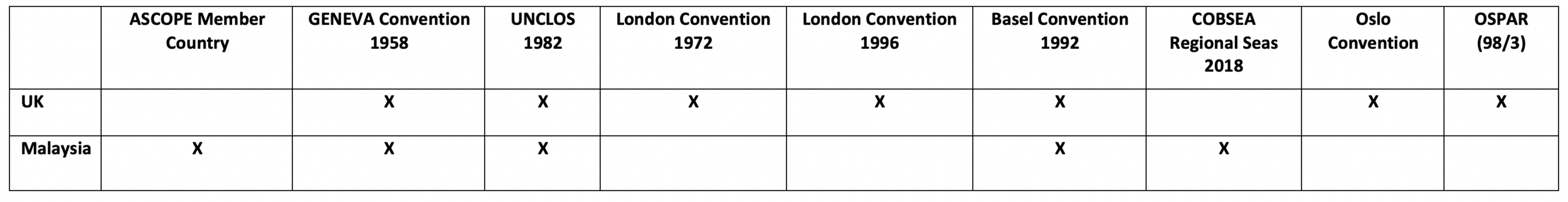

Table 1.1 Summary of Countries International and Regional Obligations

Geneva Convention

Being one of the first international treaties to directly address the abandonment of offshore oil and gas installations. Full removal being the base case for decommissioning. It also set out the following:

· No interference with fishing, Navigation and other sea users;

· Safety Zones extending up to 500m from the outer edge of facilities

· Installations which are disused to be removed entirely

· All appropriate measures to protect living resources in the sea from harmful agents

Both the UK and Malaysia are members of the Geneva Convention and as such should follow the above points when considering their decommissioning obligations. But as you will see from other more recent legislation and regulations things begin to change from the strict full removal baseline. It’s worth noting here that in 1958 offshore oil and gas exploration was still in relatively shallow waters and on a much smaller scale of the asset. Therefore, full removal was a relatively easy task to consider.

UNCLOS 1982

The convention requires signatory states to comply with the laws and regulations to reduce and prevent pollution of the sea.

· Any abandoned installations and structures are to be removed while adopting international standards established in this regard by competent international organisations. (ADG Task Force 2012)

· Such removal shall have due regard to fishing rights and duties of other states and protection of the marine environment. For any installations or structures not entirely removed, appropriate publicity is required for their depth, position and dimensions. (Oceans & Law of the Sea United Nations 2018)

As you can see the above differs from the Geneva Stance as it does acknowledge the possibility of structures not being completely removed. Both the UK and Malaysia are parties to UNCLOS. UNCLOS does not address any removal of pipelines, it has been evident in Malaysia that they are leaving the pipelines insitu following flushing.

London Convention 1972 and Protocol 1996

The original draft was 1972 and updated in 1996, the London Convention applies to all marine waters other than internal waters of states.

The protocol prohibits all dumping with the exception of a “Reverse List” to protect the marine environment from the hazards of dumping at sea. (International Association of Oil and Gas Producers, 2017).

· The Reverse List specifies Platforms as one of the specific materials that can be considered for Sea Disposal (Simlock and Wang, 2016)

· A Permit is required from the national authority and a waste assessment guide must be followed along with a set of guidelines and procedures regarding the disposal, site selection, permit management and monitoring. (ADG Task Force, 2012)

The UK is a signatory of this convention, But Malaysia is not. This is the first major difference in the two areas regimes when considering decommissioning, As has been evidenced in Malaysia with the reefing of two a Platforms, Rigs to Reefs concept is a serious consideration for Malaysia. Not being held to the London Conventions requirements for Site investigation and permitting, in theory, allows less rigorous criteria for reefing. I mentioned in the introduction that in the case of Malaysia the Polluter is also the Regulator. It is generally accepted that reefing or dumping at sea is in the vast majority of cases is the least costly option. It has also, as evidenced during the Brent Spar studies the least risk to human life from an HSE perspective. To date, Malaysia is also very much lacking the onshore facilities to decommission, although I put this down to commercial aspects rather than an unwillingness to do so.

The last environmental legislation was in 2006 and the national department for Environment (DOE) has no specific decommissioning regulations. The Waste Hierarchy is not in Malaysian Legislation and thus no consideration has to be given to reuse, reduce, recycle. It is worth noting from my personal experience with Petronas that although they are not duty-bound to consider this, they do in fact look to implement UK practices for Waste and Recycling.

Reefing in the SEA Region in comparison to the UK waters is very different. Water Temperature, Light Penetration, Depth, Biodiversity are all in contrast.

Basel Convention 1989

The Basel Convention is used to regulate the transboundary shipping of Wastes. Both the UK and Malaysia are signatories of the convention. In essence, the Basel Convention does not allow the shipping of wastes without consent from both the sending and receivers counties environmental departments consent. This was to stop the shipments of wastes to poorer countries purely for a cheaper disposal option. In the case of Malaysia, they have no site in the county capable of handling, decontaminating and disposing of NORM with a level in excess of 1brl per gram. This material, therefore, would need to be sent to a country with a facility capable of doing so. This will be sent via a TFS Note which has the pre authority from every country the material docks at or passes through.

Coordinating Body of the Seas South East Asia (COBSEA)

In brief, this promotes compliance with existing international treaties, although it does not make specific reference to decommissioning of oil and gas installations. (International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, 2017)

The UK is not part of this group for obvious reasons.

ASEAN Council of Petroleum (ASCOPE) Guidelines

The Association of South-East Asia Nations (ASEAN) has prepared the ASEAN Council of Petroleum (ASCOPE) Decommissioning Guidelines. The guidelines were drafted to complement the current decommissioning procedures rather than replace them.

The guidelines were designed to give reference points to safe operations, environmental considerations, cost effectiveness and to protect the rights of other stakeholders. It is in these guidelines that the concept of Best Practicable Environmental Option (BPEO) and an Environmental Management Plan (EMP) were introduced for decommissioning. Also of note it that these guidelines have been used by others in the absence of their own frameworks, for example, Myanmar* (Jageroos, 2018)

OSPAR & 98/3 Decision

Since 1998 the dumping, and leaving wholly or partly in place, of disused offshore installations is prohibited. However, following assessment, the competent authority of the relevant Contracting Party may give permission to leave installations or parts in place in the case of:

· Steel Installations more than 10000 tonnes

· Gravity based concrete installations

· Floating concrete installations

· Any concrete anchor-base which results or is likely to result in interference with other legitimate uses of the sea.

(OSPAR.org)

The UK is one of the OSPAR members, Malaysia is not, although it would suit the current desire to reef given that the deemed competent authority is also the contracting party.

Other Considerations

In August 2000, PETRONAS issued an overarching document entitled “PETRONAS Procedures and Guidelines for upstream Activates (PPGUA)” This serves as a guideline for decommissioning in Malaysia.

At present, there is no specific decommissioning regulations for the oil & gas industry; however, there are provisions in several Acts which decommissioning activates need to abide by. (M.l. Fam, 2018)

· Section 485A of Merchant Shipping Ordinance (19520, Which covers the safety of and control over offshore industry structures, mobile units and vessels

· Section 6 of the Continental Shelf Act (1966) – Stipulates new regulations for the removal of abandoned or disused installations.

· Section 23 of the Economic Zone Act – Stipulates any disused cables or pipelines need to be informed to the government and if directed to do so, must remove them.

· The Environmental Quality Act 1974 – Prohibits oil discharge and wastes into Malaysian Seas

· Environmental Impact Assessment Guides – States the requirement to submit an EIA prior to works

· MARPOL 73/78 protocol is also a consideration for both the UK and Malaysia.

IMO guidelines with MER in the UK following the Wood Report

Conclusion

Overall the international regulations give a very similar basis for both countries, although with the UK having many Stakeholders and a vast number of concerned authorities, I would consider the strength of these to be greater in the UK than Malaysia. I would also conclude that on experience the court of public perception is greater in the UK than Malaysia, meaning that the best environmental options are expected to be pursued rather than the best cost. PETRONAS being the regulator along with the ASCOPE guidelines of BPEO and the fact that they are not part of the London Convention on Dumping allows Reefing to be considered more than in the UK waters.

For me, there needs to be more studies done on the benefits of reefing before I conclude which is considered a better approach.

I would argue that the UK decommissioning capabilities are much more established not just because of the more robust regulations but from a clearer stance on what can be done. Industry invests in people, technology, research and infrastructure when the future marketplace is known and quantified. In the UK we know that a significant amount of works will be done onshore, so companies have invested to be able to capture part of this market. In Malaysia, the end destination and timescales for decommissioning are still under discussion. A preference for reefing has been established at this stage and thus the country lacks onshore facilities and waste infrastructure. So, from this point of view, we can conclude that the UK regime is better for the industry. Also following the Wood report the guidelines which established the Oil and Gas Authority along with the inclusion of Maximum Economic Recovery, aid the UK understanding and decommissioning policies.

References:

LAWS OF MALAYSIA – Petroleum Development Act 1974 – as of 1 June 2013

SPE-193946-MS, Steve Laister and Sylvia Jageroos, Different Routes – Same Destination: Planning Process for Decommissioning in South East Asia

Oceans & Law of the Sea United Nations 2018

ADG Task Force 2012

Ocean Engineering – A review of offshore decommissioning regulations in five countries – Strengths and weaknesses – M.L Fam, D Konovessis, L.S Ong, H.K Tan

JULY 15, 2015 - Low oil price domino effect to shut more North Sea fields early- Claire Milhench.

Ospar.org